The Origins of Pride: Stonewall Uprising

The Origins of Pride: The Stonewall Uprising

This page documents the true events surrounding the 1969 Stonewall Uprising using only direct quotes, primary source accounts, and historically verifiable records. It aims to provide clarity amid decades of retrospective embellishment and misrepresentation.

Background: Pre-Stonewall Conditions

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, laws across the United States criminalized homosexual conduct. In New York, public morality codes allowed for the arrest of individuals not wearing at least three articles of clothing appropriate to their biological sex—a tool often used to target drag performers and gender non-conforming individuals.

Most gay bars, including the Stonewall Inn, operated illegally under Mafia control. The Stonewall lacked basic amenities like running water and clean glasses, but it provided a rare refuge for marginalized people, especially homeless youth, drag queens, and gay men.

Police raids on these establishments were common, typically involving arrests for cross-dressing, solicitation, or liquor violations. Until Stonewall, such raids were met with passive compliance.

June 28, 1969: The Night of the Raid

In the early hours of June 28, 1969, the NYPD's Public Morals Division raided the Stonewall Inn. Officers entered with a warrant, citing unlicensed alcohol sales and violations of gender presentation laws. Patrons were ordered to produce identification and subjected to physical searches. Several were detained.

Unlike previous raids, this time the crowd resisted. Hundreds gathered outside as the situation escalated. The turning point came when a butch-presenting lesbian—widely believed to be Stormé DeLarverie —struggled against officers, shouted to the crowd, and allegedly asked, “Why don’t you guys do something?” The crowd responded.

The Riots Begin

What began as verbal resistance rapidly escalated. Eyewitnesses reported bottles, bricks, and debris being thrown. Trash cans were lit on fire. NYPD officers retreated into the bar and barricaded the doors as the crowd outside grew increasingly hostile. Eventually, the Tactical Patrol Force (TPF) was deployed to suppress the riot. Protesters chanted slogans and resisted dispersal.

The uprising continued over several consecutive nights. Each evening brought renewed demonstrations, further confrontations with law enforcement, and a growing sense of collective resistance.

Who Was Involved

Despite modern claims that the uprising was led by “trans women of color,” historical evidence shows the participants included a broad coalition:

Gay men and lesbians

Drag queens and transvestites (biological males in feminine clothing)

Homeless youth engaged in survival sex work

Local residents and allies

Notable individuals confirmed or widely believed to have been present include:

Stormé DeLarverie (a biracial drag king and lesbian)

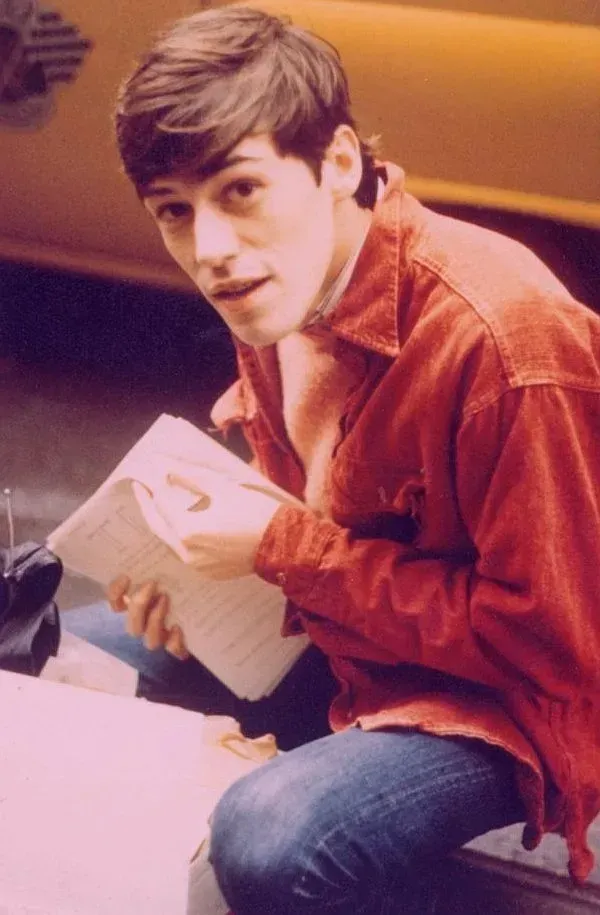

Fred Sargeant (gay activist and later co-organizer of the first Pride march)

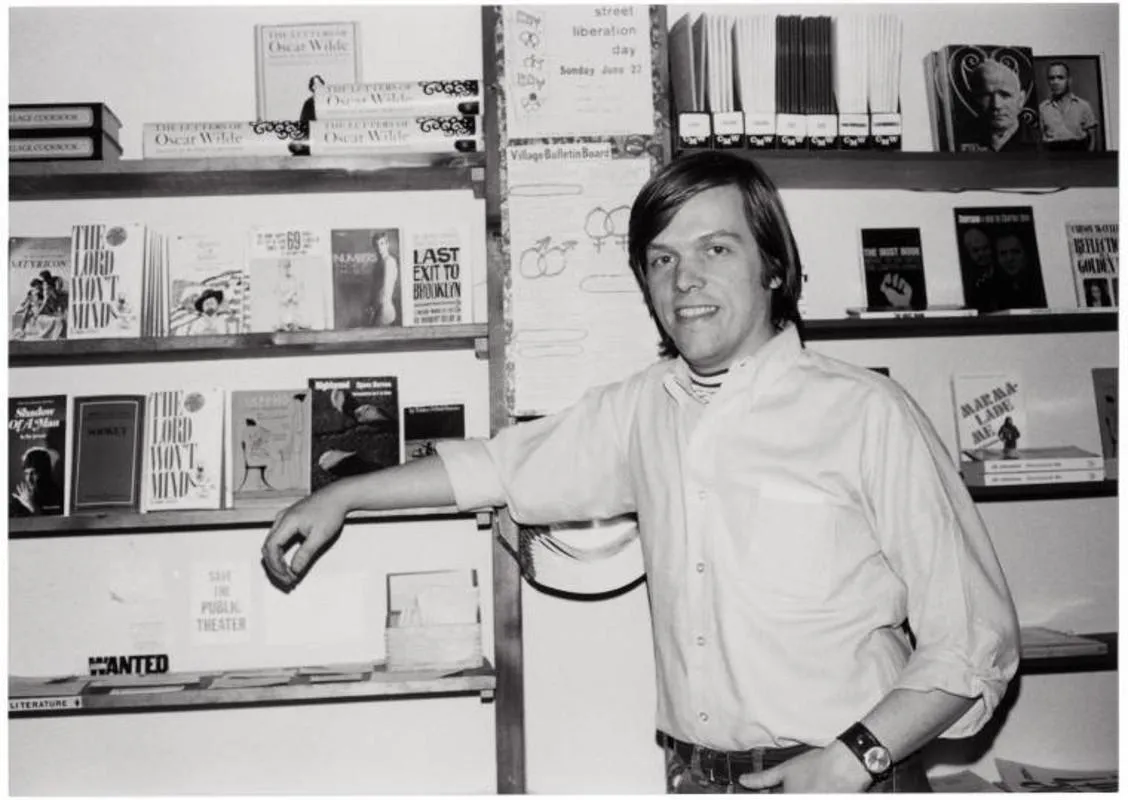

Craig Rodwell (gay bookstore owner and early activist)

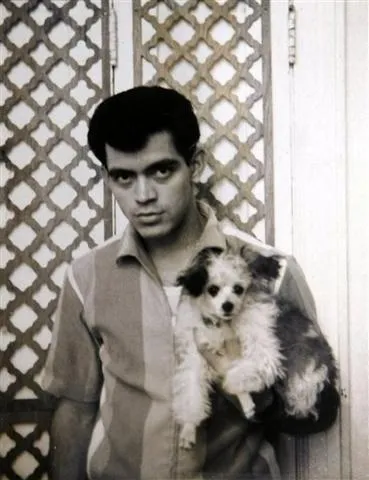

Raymond Castro (gay man arrested that night)

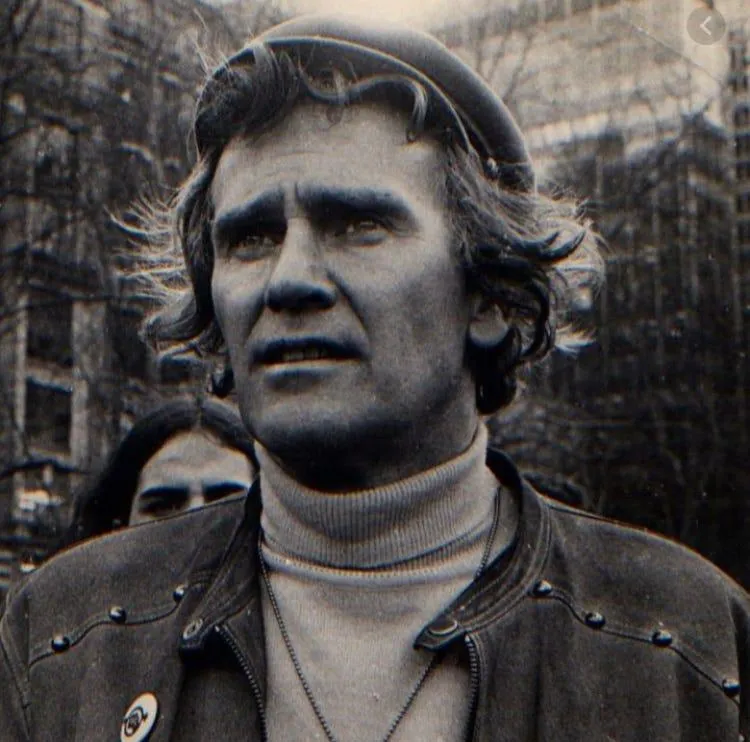

Bob Kohler (Village resident and activist)

Why Stonewall Matters

While not the first act of LGBTQ+ resistance—earlier protests had occurred at Cooper Do-nuts (1959), Compton’s Cafeteria (1966), and the Black Cat Tavern (1967)—Stonewall was the first to spark a sustained and organized movement. It marked the beginning of large-scale, public advocacy for gay rights in the United States.

It is important to honor this history accurately, without imposing modern ideological frameworks onto past events or individuals who identified differently than current categories suggest.

Works Cited

History.com Editors. “What Happened at the Stonewall Uprising?” *History.com*, A&E Television, June 25, 2019. history.com

Cited for details on police raids targeting cross-dressing patrons, Mafia control of Stonewall, and the escalation of protests after the June 28, 1969 raid. Confirms timeline, crowd behavior, and emergence of sustained unrest.

Library of Congress. “Today in History: June 28.” *Library of Congress*. loc.gov

Verifies the exact timing of the raid (around 1:15 a.m.), use of a search warrant against unlicensed alcohol, involvement of Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, and eyewitness accounts describing resistance and prolonged riots.

Malinda Lo. “The Legendary Stormé DeLarverie.” *MalindaLo.com*, June 3, 2021. malindalo.com

Documents the crucial moment when Stormé DeLarverie resisted arrest and shouted, “Why don’t you guys do something?”—sparking the crowd’s resistance. Used to verify her identity and role in igniting the uprising.

Britannica. “Stonewall Riots.” *Encyclopedia Britannica*. britannica.com

Provides an overview of the riots’ origins, actions of the Tactical Patrol Force, continued multi-night protests, and Stonewall’s transformative impact on LGBTQ+ rights and the formation of Pride.

History.com Editors. “How Dressing in Drag Was Labeled a Crime in the 20th Century.” *History.com*, A&E Television, June 2, 2025. history.com

Used to explain the "three-article rule" in New York, showing how cross-dressing laws were enforced and used to justify police raids on venues like Stonewall.

Note: The following section represents the author's opinion and interpretation based on cited primary sources, interviews, and historical records documented in previous sections.

My Thoughts

Who Was Really at Stonewall — And Why the Truth Matters

In the decades since the 1969 Stonewall uprising, the public has been sold a feel-good narrative polished for modern activism — a story that centers drag queens, transvestites, and “trans women of color.” But when you strip away the slogans and dig into the actual police reports, arrest records, firsthand interviews, and contemporary journalism, that version of history doesn’t hold up. And rewriting history for political convenience doesn’t just disrespect the truth — it erases the people who were actually there.

Let’s set the record straight.

Raymond Castro, a gay Puerto Rican man, was one of the few people confirmed to have been arrested that night. His physical resistance during the arrest was one of the first acts that caused the gathered crowd to push back. Stormé DeLarverie, a biracial lesbian and drag king, is widely believed to be the woman who scuffled with police and shouted to the crowd — “Why don’t you guys do something?” Her story is corroborated by multiple eyewitnesses, and even if she’s not listed by name in the reports, the accounts align. Dave Van Ronk, a straight male folk singer who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, was arrested by police during the chaos. These were real people in a real moment — not activists looking for legacy, but humans who resisted, reacted, and in some cases, were brutalized.

Meanwhile, the names most people have heard — Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and Miss Major Griffin-Gracy — were not there when the riot began. Johnson himself stated in multiple interviews that he arrived at the Stonewall Inn around 2 a.m., well after the police raid had already taken place and the crowd had started rioting. He explicitly said, “I didn’t get there until the place was on fire.” Rivera’s story changed over time, and his presence was publicly disputed by multiple people including Johnson and longtime Village activist Bob Kohler. Records suggest Rivera may not have even been out of jail at the time. Griffin-Gracy, likewise, claims to have been there and arrested, but has acknowledged memory gaps and provides no verifiable evidence of being present. Other names like Zazu Nova and Yvonne Ritter appear in retrospective oral histories decades later — with no arrest records, police mentions, or eyewitness accounts placing them there.

So where did the myth come from?

Over time, as Pride became institutionalized and aligned itself with broader identity politics, the focus shifted. The truth — that the crowd included primarily gay men, lesbians, and some street kids — was rewritten to spotlight drag queens and “trans women of color,” even when the individuals in question either did not identify that way at the time or weren’t even present. This wasn’t an organic shift; it was deliberate. Movements looking to gain moral leverage reshaped the narrative for their cause. But moral leverage built on fiction is still fiction.

Some of the most important figures in the gay rights movement didn’t even participate in the riot itself — but they organized its aftermath. Craig Rodwell, who founded the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, and Fred Sargeant, his partner, helped turn a spontaneous act of resistance into a political movement. They co-organized the very first Pride march in 1970, called the Christopher Street Liberation Day. Neither man was inside the Stonewall Inn when the raid took place, but their legacy is grounded in action — not mythology. Bob Kohler, a longtime gay rights and civil rights activist, lived nearby and supported early movement efforts but was not a participant in the riot. Inspector Seymour Pine, on the other hand, was the NYPD officer who led the raid. He later expressed public regret and confirmed many of the night’s events in interviews.

This isn’t about taking away credit. It’s about giving it to the right people. When we distort the past to fit current political narratives, we do two kinds of damage. First, we rob the real participants — like Castro and DeLarverie — of the recognition they earned. Second, we teach the next generation a lie. That’s not justice. That’s propaganda.

And that propaganda has consequences.

In recent decades, activists have increasingly claimed that “trans women of color started Pride.” This claim is not supported by primary sources, arrest records, or firsthand testimony — and yet it has been elevated to the status of historical fact in schools, media, and public discourse. The goal is not historical accuracy. The goal is cultural conditioning.

This isn’t just a case of misremembering — it’s a strategic revision of history. By rewriting the origins of Pride to center transgender identity, activists have created a narrative that retroactively legitimizes today’s aggressive push for gender ideology, particularly when it comes to children. We're no longer just talking about equal rights for adults — we're talking about puberty blockers for confused kids, irreversible surgeries on minors, and psychological manipulation that tells boys they might really be girls, and vice versa.

Why is this happening? Because movements like this require a society without strong men, without protective fathers, and without cohesive nuclear families. It’s no coincidence that the modern push for radical gender theory emerged alongside movements that treat masculinity as toxic, fatherhood as optional, and traditional families as oppressive relics of the past. A divided, destabilized culture is easier to control — and a society without strong male leadership is one that won’t push back.

The truth is this: if the nuclear family were still intact — if boys were encouraged to grow into men instead of being chemically castrated or socially shamed — much of the chaos we’re seeing wouldn’t have the foothold it does now. There may not be a single cause for every cultural collapse we’re witnessing, but there is undeniable correlation. The weakening of men, the breakdown of families, and the erosion of truth are all connected — and this movement thrives in that wreckage.

Stonewall was not about any of this. It was about people who were tired of being harassed and abused by police. It was a demand for dignity, for space, for protection under the law. What it was not — and what history does not support — is a celebration of gender confusion or a greenlight for the medical mutilation of children. The people who fought at Stonewall wanted to be left alone, not worshiped. They wanted truth, not propaganda.

We owe them honesty. We owe our children protection. And we owe our culture a spine.